Finesse Johnson Stewart '25 wants an education in the global fight for social justice. Instead of just reading about notable figures in the history books, she went to speak with them.

The chilling image of Hector Pieterson's lifeless body has become an icon of the Soweto uprising, representing the nearly 200 children killed by police during the bloody protests in South Africa in June of 1976. Black school children, from various schools in the Soweto township, revolted against the introduction of a racist, oppressive (and in an era of apartheid, unsurprising) policy in their education. Police showed no mercy in quashing the protests with gunfire. Pieterson, only 12 years old, was among the victims, and famously photographed as his sister Antoinette Sithole ran by his side. Nearly a half century later, Finesse learned about that day directly from Sithole.

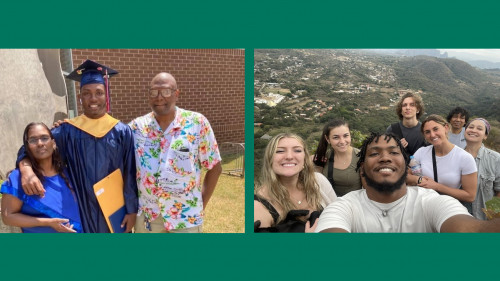

Finesse's study abroad program – through the Asbury University Center for Global Education and Experience – is called Decolonizing the Mind. She spent the first few weeks in South Africa and just recently transitioned to Namibia for the balance of the semester. Apartheid – which was a system of institutionalized segregation – was the only way of life in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) for the second half of the 20th century. Finesse's education is an up close look at the sins of apartheid, its unimaginable cruelty, and the lingering effect.

"This has been a transformative experience and one of personal growth. There's a lot of truth to hear and digest. When it comes to understanding the pursuit for social justice around the world, it doesn't get any better than hearing it from the people it happened to."

Finesse spoke with Sithole at a museum. She visited Robbin Island, a prison off the coast of Cape Town where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned, and talked with a tour guide who was sent there as a prisoner at 14 years old. She saw the bullet holes in Regina Mundi church, made by police while firing at children who were seeking refuge during the Soweto uprising.

"I kept asking people, 'How can you stand there and tell your story, and not be mad?' I learned that it's hard to deal with, but they kept telling me these are stories that need to be heard."

Finesse doesn't want to just listen, she wants to be a force in the fight for change. Part of the reason Finesse, who is part of Siena's Higher Education Opportunity Program, chose the Decolonizing the Mind program was because of the internship. On Monday, she began working with the Namibia Institute for Democracy, which runs anti-corruption and voter education programs.

"This experience fuels you to want to fight for better. Seeing that there's an organization here trying to stop history from repeating itself, I'm grateful for this opportunity."

In South Africa, Finesse saw the scars left by apartheid, but she also marvels at the country's beauty. "Social media," she says, "doesn't do Africa justice in capturing its beauty." In the same way, reading about segregation doesn't do the horrors of apartheid justice. Sometimes, you just have to go and see it for yourself.